The wines of Valencia

Valencia is known worldwide for its oranges, but its long days of warm sun and position next to the Mediterranean Sea also make it an ideal place for growing grapes. Generally speaking, Valencian wines tend to be intense, with body, structure and a relatively high alcohol content. Within the general region, one can distinguish seven or eight main wine producing areas, each with its own specific topography, climate, and very often its own dominant grape variety, resulting in an array of very different wines.

The Alto Turia, for example, an area at 500-1000 meters altitude, is known for the white Merseguera, which produces wines with relatively high acidity. The low-lying regions near Valencia City and in Alicante are known for Moscatel, a very aromatic white wine. The Terres dels Alforins valley, aka the “Tuscany” of Valencia, is known for its high-quality red wines. To the west, en route to Madrid, the Utiel-Requena region is famous for reds from the indigenous Bobal grape as well as quality cavas. In the warmer south, around Alicante, the Monastrell grape is used for powerful dry reds, as well as the historically significant Fondillón, the sweet ‘wine of kings’, which in the 17th-18th century, was exported all over the world. In short, there is a huge wine world to discover here in Valencia!

A selection of the best Valencian wines.

This is the first in a series of articles on Valencian wines; it’s a basic introduction to its history and the national classification system for wines. In the next articles we will look more closely at the different wine regions in Valencia, the most common grapes and Valencia’s best wines.

A Brief History

The Valencia region has a long history when it comes to wine making. There is evidence that even 2700 years ago people were already producing wine here, as shown in excavations in the Utiel-Requena area. The Iberians learned the art of making wine from the Phoenicians (from around 800 BC) and the Greeks (from around 600 BC), who also introduced new grape varieties.

In the early days, most wine making was for home consumption, but over the years it became more and more a commercial activity. Wine making in Spain got an incredible boost in the 19th century with the arrival in Europe of ‘Phylloxera‘ from North America, a small insect that feeds on the roots of the vine, eventually killing it. It was first seen in the UK in the 1850s and in the 1860s appeared in France, where, within 15 years, it destroyed more than 40% (eventually possibly even more than 75%) of the vineyards. The desperate French came to Spain to buy wine. Nearby Rioja especially benefited – within 20 years they had doubled their wine production.

But other regions benefited as well, including Valencia, and in particular Utiel-Requena; in the 1880s a railway was built from Utiel to the Valencia port, just for the purpose of exporting its wine. It was during this time of growth that the Bodega Redonda was built right in front of the railway station. Nowadays it is the headquarters of the regional wine authorities, and a wine museum.

Of course, Phylloxera did eventually also come to Spain, appearing first in 1878 in Malaga, and in Valencia at the beginning of the 20th century, but by then, some solutions had been found. Since Phylloxera had evolved in North America, its vines had evolved along with it, and many were therefore resistant. Many winegrowers had started using hybrids, a cross between American and European grape varieties. Since most American grapes don’t produce wine that most consider enjoyable however, another solution was developed. Winegrowers learned that by grafting the European vine onto resistant American rootstocks, they could achieve a resistant plant, that was capable of producing European grape varieties. This method is still practiced today, almost universally around the world.

In general, the quality of Valencian wines was not very high. Wine was produced for export and possibly to mix with other wines. Indeed, even until the end of last century Valencia did not produce much in terms of quality (with the exception being Fondillón). That reputation continues today, as a stigma maybe, even within Valencia. But in the last two decades the quality of Valencian wine has improved drastically, and award winning wines are now being made in the region. Improved technology has contributed to this, but probably also a growing demand within Spain, Valencia and Europe for quality wine. Nevertheless, it is still hard to find good Valencian wines in shops and restaurants, though this has also improved in the last years.

The Classification System

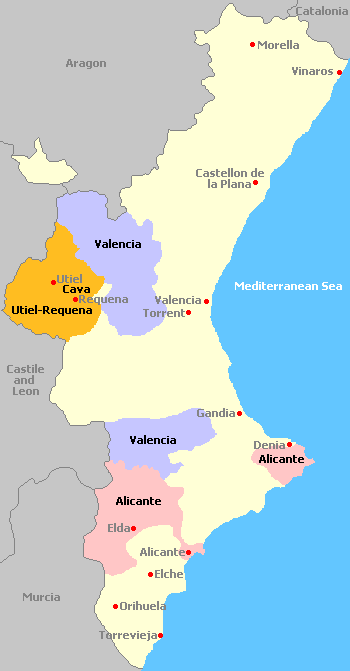

The Comunidad Valenciana has several wine producing areas: Castellón, Valencia, Utiel-Requena and Alicante.

Valencia Wine Regions. Source: http://www.wineandvinesearch.com/

As in the rest of Spain, each of these regions has its Denominación de Origen Protegida or DOP, (Protected Denomination of Origin), similar to the French “appellation controlée”, governed by a semi-autonomous Consejo Regulador. Its purpose is to monitor and guarantee the quality and the geographical origin of the wine. Castellón is not yet a full DOP, but rather an Indicación Geográfica Protegida or IGP (Protected Geographical Indicator) – similar to a DOP but less strict.

The only exception to this regional classification is the DO Cava, which monitors a method of production (of cava), rather than a region of production. The village of Requena is the only area within Valencia to hold DO Cava status. As such, its wineries are the only ones in the Valencia territory allowed to call its sparkling wines ‘cava’; all the others have to call it ‘espumoso’ . This doesn’t indicate necessarily the quality of their sparkling wine; some espumosos could be better than some cavas.

In 2003, another category, “Vino de Pago” was added to the classification system. A ‘pago’ is a plot, or vineyard. To be of significance, a “pago” is supposed to have some characteristics that differentiate it from others, including a particular microclimate, while the vineyard must be known locally under a certain historical name, and lie within the boundaries of a single municipality. If the winery can prove that the wine from this vineyard (and made only with grapes from that vineyard) is something special, different, or specific for that vineyard, it can request (from the local wine authorities, the Consejo Regulador of the DO) the status of ‘vino de pago’ for that particular wine from that particular vineyard. It does not mean that all the wines of that winery are ‘vinos de pago’, nor does it necessarily mean that it is a high-quality wine, even though the wineries that produce ‘vino de pago’ like to present it as such.

There are also wines in the market that put “Pago de …” on their labels – in most cases this is simply the name of the wine, with reference to the name of the vineyard; these should not be confused with a true ‘vino de pago’, which is the only wine that can have “vino de pago” on its label (see image).

Label of a ‘vino de pago’, Finca Terrerazo from the Utiel-Requena area.

Currently there are less than 20 approved vineyards that can produce vinos de pago in the whole of Spain; five of them are in Valencia: the wineries of Mustiguillo, Vegalfaro, Vera de Estenas, Chozal Carrascal and Pago de Tharsys all produce one or more vinos de pago, and are worth trying!

This article first appeared in April 2016 in the Lens Gourmand blog

Sin comentarios